For a better understanding of Bernstein’s position in the world of conductors, let us now first have a look at the history of conducting. The history discussed below will focus on how time inaudible time beating – as opposed to audible time beating with a stick on a music stand or the ground -, emerged and orchestral conducting as we know it stemmed from that practice. Orchestral conducting is such a young profession that the development of going from time beating to what conducting entails these days is trackable on video recordings. This development is one of the key interests of these research, which is why this part of history will be discussed. There is much more to tell about the history of conducting, but that will not be adressed further in this research.

History of conducting

Conducting is mostly concerned with Western music, where it originated.1Spitzer, Conducting Orchestral conducting is a relatively young profession as it is tied to the developments of orchestras an orchestral music.

The concept of an orchestra, a large grouping of instrumentalists, was born between about 1680 to 1740, the latter part of the Baroque period (roughly 1600 – 1750). 2Spitzer et al., Orchestra, 5. The birth of the orchestra (1680–1740); Palisca, Baroque Instrumentalists started to specialize in playing one specific instrument rather then the lot of them. Then the number of strings players in ensembles increased, and other instruments started to join as well. Usually, a violinist was the designated leader who was in charge of setting tempos and deciding on bowings for the string instruments.3Spitzer et al., Orchestra, 5. The birth of the orchestra (1680–1740) When playing such Baroque music, little metrical supervision is needed, whether played back then or by a modern orchestra that is used to playing under leadership of a conductor.4Galkin, A History Of Orchestral Conducting; In Theory And Practice, 7 Baroque music contains rhythmical features such as symmetrical phrase length and regularity of beat that make external regulation of tempo needless.5Galkin, A History Of Orchestral Conducting; In Theory And Practice, 7

However, since the Classical period (roughly from 1750 to 1820), other roles have been assigned to rhythm. Composers started to affirm the rhythmical aspects of Baroque music, and began to obscure the characteristics of metrical regularity.’6Galkin, A History Of Orchestral Conducting; In Theory And Practice, 7 ‘Freed in their orchestral music from the keyboard, Mozart and his contemporaries distributed the constancy of the beat by exploiting syncopation; its effect as described by Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) was to “shock the ear.”‘7Galkin, A History Of Orchestral Conducting; In Theory And Practice, 7

The composers of the Romantic period (nineteenth century) continued this trend of destabilizing rhythm, and took things a step further, which eventually resulted in the birth of orchestral conducting: ‘Confronted by new and sometimes perplexing rhythmic challenges, nineteenth-century orchestral musicians were forced to depend more and more on a central authority to assist them in their performance: the conductor. Simultaneously, it became his responsibility to develop a technique of direction, making possible control of such music in terms of all its rhythmic and metrical intricacies and expressive implications.’8Galkin, A History Of Orchestral Conducting; In Theory And Practice, 12

This was the start of modern conducting as we know it: one leader standing on front of the orchestra who beats time in a visible but not audible manner. To this end, orchestral conductors often but not always make use of a baton, a short stick, in their dominant hand. This practice came to be at the beginning of the nineteenth century, where Spontini, Spohr, and Weber started to adopt the practice of (inaudible) baton conducting and take complete leadership at the rehearsals and concerts.9Bowen, The Cambridge Companion to Conducting, 117

As the years went by, conducting technique became more and more elaborate and finetuned: what started out as beating time to keep the orchestra together, now included more gestures to express i.a. articulation and the feeling of the music. After all, that was what leading a rehearsal, also before conductors came along, was always about: someone, before the conductors came about an instrumentalist or composer, had to take authority and decide for the entire ensemble how the music would be interpreted and performed. This part of leading the rehearsal got increasingly more included in the conductor’s gestures.

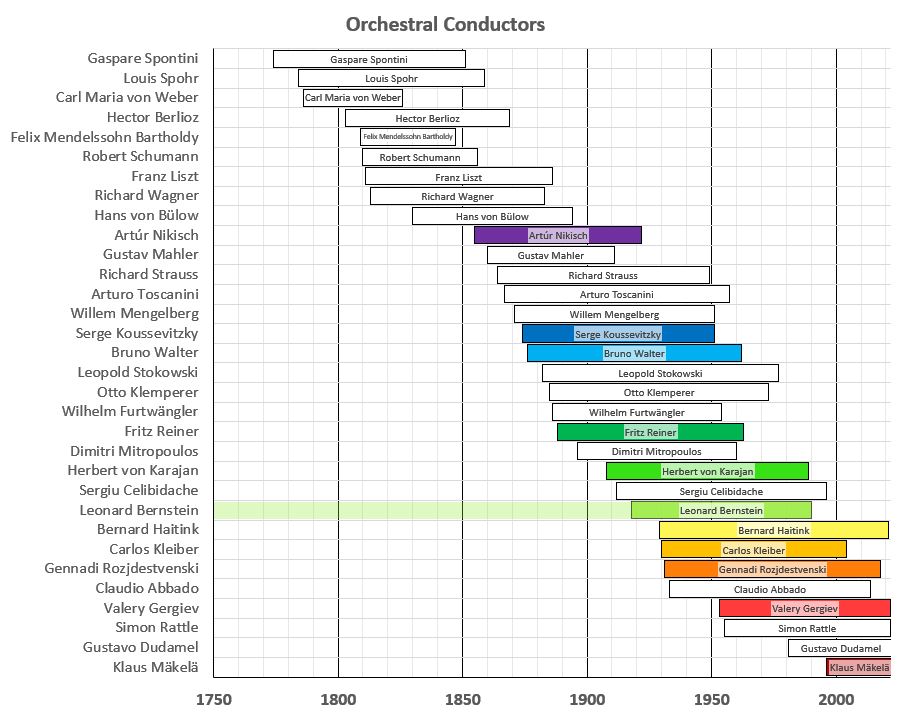

Figure 3.1. displays a compact timeline with famous conductors throughout history, starting from the point where inaudible baton conducting emerged. From the twentieth century on, one can see a shift in practice from composer-conductors, roughly until Richard Strauss, to conductors who are specialized in conducting only. Bernstein is actually an interesting exception to this trend, as the only well-known composer on the list of conductors in figure 3.1 after Strauss.

Fig. 3.1. Timeline of Orchestral Conductors

All conductors that are discussed in this project can be found on this timeline. Some names are colored for the purpose of finding their names easier. This does not however imply in any way that these conductors are of more importance than others. They are merely discussed more in this research.

Principles of conducting

What does a conductor do?

The art of conducting has numerous sides to it, ranging from giving simple functional instructions of tempo to creating a comfortable and efficient work working atmosphere for the musicians involved. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians explains orchestral conducting as consisting of three main tasks:10Spitzer, Conducting

1. leading the orchestra in rehearsal and concert

During rehearsal, the conductor decides what the orchestra is going to play when and how. They correct mistakes, indicate how the music should sound, and assists the orchestra by showing aspects like tempo and expression in their gestures to get all the orchestra members to play in time and with the proper expressions. Leading the orchestra during rehearsal has two parts to it:

a. conducting technique: the gestures the conductor makes while conducting to indicate tempo and express other musical ideas

b. rehearsal technique: deals with the structure of the rehearsal (i.a. what piece to rehearse first, whether you initially play through the entire piece or stop the first time halfway to rehears a certain passage), and how and what to verbally communicate with the orchestra (help the violins and flutes to play together by telling them that they are together, help the strings keep tempo by informing them that the bas drum indicates the beat, help the wind players project by asking them to picture the audience at the back of the hall and imagine their sound reaching all that way)

2. interpretation of the music

There are always multiple interpretations possible of the same piece of music, and it is up to the conductor to decide which way the orchestra should perform it. This includes for example the tempo of the piece, how loud to play in which moment, what tone color to use, and what the general mood should be.

3. participation in administration of the ensemble

Outside of rehearsals, concerts, and studying and interpreting the music, the conductor also takes part in governance of the orchestra. The exact number of tasks varies from orchestra to orchestra (especially between amateur and professional orchestras) but it usually entail things like deciding on repertoire or making a seating plan for the orchestra.

This research will focus solely on the ‘conducting technique’ aspect for that is the part of the job where the actual music making happens. The remainder of this chapter will provide a more detailed explanation of what ‘conducing technique’ entails. Once we are all up to date on those conducting basics, we can go explore what kind of conductor Bernstein was in the next chapter.

The general workings of conducting

Conducting techniques consist of two fundamental principles: preparation and expression. The first fundamental principle, preparation, is about when to give what instruction. Instructions come inherently before the action that is to be taken; therefore the conductor’s movements must anticipate what is coming in the music. If the conductor would only be showing what is happening in the music in that moment, they would basically be telling people what to do on the moment there are (supposed to be) doing it, which by definition is too late. Hence, preparation is key. This allows the musicians to actually assignment and follow up the command.

That said, there are certain aspects the conductor will show ‘in time’. When beating time for example, the actual beat should always be in time with the beat of the orchestra. However, in order to signal to the orchestra that the beat is coming, the conductor will make a falling movement. People are very good in perceiving the natural gravitational acceleration and therefore are able to predict when a certain object will hit the ground when it is falling. The conductor will use this principle by (in theory) always landing the beat on the same horizontal line. This way, the musicians inherently know when the beat will come, and can check themselves ‘in time’ for the conductor will of course also actually ‘hit’ the beat.

The second fundamental principle is expression. Where preparation shows the musicians that something is coming and when it is coming (by proper timing of the conductor), expression informs the musicians of what it is that is coming or happening right now. There is a more or less standardized grammar of conducting, although there are many variants on for example beat patterns, but these same fundamental principles apply to all of them.11Rudolf, The Grammar Of Conducting; Nowak et al., Conducting the music, not the musicians Even the absence of these principles can be a signal in itself: by for example not showing any gravitational acceleration thus performing a very non-active movement, the conductor can make an entry intentionally vague as to get an effect where the musicians don’t come in at the exact same moment resulting in a beautiful intangible beginning. Furthermore, the same principles of preparation and expression are visible too in some conducting performances that lack any standardized beating pattern of sorts. In the end the exact gesture or direction of movement is not important: as long as these two fundamental principles are used properly, any gesture will be effective.

Moreover, conducting is not just about telling musicians (verbally or non—verbally) what to do, but also to create the right atmosphere for them to work in. If you cue the orchestra to start and the just stand still in front of the orchestra for the entire performance, you will be troubling the orchestra because you express something different from what they are supposed to play, even if they don’t need you to beat time or cue entries. (Nota bene: doing nothing is a signal in itself.) Therefore, beating time in a way that suits the expression of the music is in that case way more helpful: it allows the orchestra to join the conductor’s flow, so they’ll be rowing downstream instead of upstream against the conductor’s silence. In the same way, musicians will often appreciate the conductor cuing their entrance, even if they are 100% sure where they should come in. The conductor’s confirmation will make them feel safe so they can fully concentrate on the music. Lack of confirmation will leave them in doubt at least a little bit, which doesn’t help the musicality of their performance, and sometimes (especially in the amateur scene) leads to musicians being so confused that they do not come in whatsoever. This conformation can be very subtle as well, the slightest head turn by the conductor in your direction, without them actually making eye contact or cuing your entrance with their hand, can suffice as a signal of acknowledgement that you are supposed to come in.

Function VS expressive quality of gestures

When discussing the conducting techniques of various conductors in the next chapter, I will make a distinction between the functionality and expressiveness of certain gestures they make. When talking about functionality, I refer to the information the gesture conveys that is not dealing with expressiveness but with ‘dry’ musical information such as rhythm, timing, and what beat of the measure it is. When talking about expressiveness I refer to the emotional information the gesture conveys such as articulation, tenderness, expressive vibrato, agitato feeling, etc. Those two aspects go hand in hand and are always both present in every gesture, to varying degrees: lack of any sign of emotion is in itself also an expression of emotion, and lack of a perceptible sign of timing is in itself a means of creating a non-strict timing. In quantity of presence in a gesture these qualities are however completely independent of each other: whether a gesture is not really or very functional does not have an impact on how expressive it is. However, a more functional gesture is not always more effective. The conductor must always be self-critical and wonder whether their gestures are conducting the musicians (give all the instructions you can) or conducting the music (only make gestures when the music asks for it, and that reflect the music).

The ability to give imprecise instructions can be just as necessary and effective as precise gestures. It often is that concept of being perfectly imperfect, that makes a good music performance. Any symphony with all the tutti chords played exactly at the same time would sound horrendous. Barber’s Adagio for strings would be way less moving if all note changes would be perfectly in sync: that would create hard lines that disturb the carefully constructed long lines. This list could go on endlessly, as it is not just about timing of entries, but also timing of rhythm and tempo (think of rubato!), dynamic changes, and more. It is one of the important aspects of what sets life performance apart from auto-generated recordings.

Now we will go into the meanings behind the variety of gestures a conductor can make as we explore ‘the 8 basic principles of conducting’. Nota bene: these are different from the 2 fundamental principles of conducting technique.

The 8 principles of conducting

The basic principles of conducting include the following:12Rudolf, The Grammar Of Conducting. v – viii

-

- general appearance

- beat patterns

- use of left/right hand

- dynamics

- articulation

- phrasing

- use of the eyes and facial expressions

These are features you will find in any textbook about conducting technique, such as The Grammar Of Conducting by Max Rudolf or Conducting the music, not the musicians by H. and J. Nowak. In the analysis of various conductors I will use these seven principles to compare different conducting styles, with the addition of one extra point in which I will discuss the conductors idiosyncratic gestures:

8. quirks

Below follows a general description for each of these eight principles:

1. General appearance

This is a bit of a mystical aspect of conducting. Why do some conductors seems to radiate music without moving a single muscle, while others beat perfectly neat measures and feel uninspiring? It has a bit to do with posture, bit with facial expressions and eye contact, and probably for a considerable amount also your personality. People never seems to be able to put their finger on it, what it is that a great conductor does that distinguishes them from one that is just very good. In some way or another it has to do with their general appearance. In many an anecdote the presence of a conductor makes all the difference without them actually conducting.

As this is the more intangible part of conducting, it is more difficult to show. I find it most apparent in conducting masterclasses where there is often a striking difference in charisma between master and pupil. This is of course not a fair representation variation in ‘general appearance’ between conductors due to the discrepancy in experience. It does however hopefully provide insight in how conductors all have their own aura and how that on its own – conducting techniques aside – makes a difference in what kind of conductor they are.

In the video below, Valery Gergiev is giving a masterclass to Alexis Soriano. Despite the fact that Soriano is conducting and not Gergiev – although Gergiev can ‘t help himself and still pitches in now and then -, Gergiev still seems to be the most present leader without doing more than being actively present (being with the musicians in full attention).

Vid. 3.1. Gergiev & Soriano, Scriabin Poème de l’extase13Ruben Diaz Flamenco Guitar, The Great Valery Gergyev Teaching How To Conduct Scriabin (Master Class) Скрябин / Валерий Гергиев, [42:49]

2. Beat patterns

Beat patterns are chorographical patterns conductors use to indicate the beats in a bar by displaying those patterns with their hand. For different same signatures there are different patterns, but they are all based on similar principles: one makes a falling motion imitating the earth’s gravitational acceleration towards a beat and then decelerates when leaving that beat. Furthermore, the directing from which one approaches the beat indicates which count of the bar that beat falls on. The gravitational acceleration allows the viewer to predict when the beat comes, as humans are used to see things fall to the ground on earth. The conductor just has to make sure that the tact points are on the same height so the viewer knows where the falling motion will end, and then they’ll be able to predict precisely when the beat is.

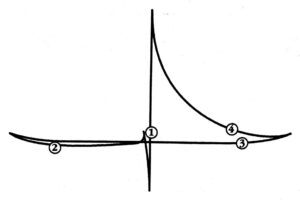

Below we see again neutral-legato 4/4 beat pattern from the introduction of this research.

Fig. 3.2. Neutral-legato 4/4 beat pattern14 Rudolf, The Grammar Of Conducting, 9

Note how the tact points – the circled numbers that represent where each beat is – are not on the same horizontal line. See also how the pattern goes below beat 1, but does not do so with the other beats.

Although the general idea of this 4/4 beat pattern is standardized, there are countless variations on the execution. The direction of movement (move down towards the beat) and orientation of the beats (beat 2 is on the left side of beat 1 from the conductor’s point of view) is always the same, but there is for example no consensus on whether to stop moving downwards as soon as you reach the beat, or go on like after the first beat in figure 3.2.

Below, conductor Leonard Slatkin shows how to beat a 4/4 beat pattern. As opposed to the graph above, he prefers not to move below the tact points (so he does not go below the line), except for the preparation of the 4th count. This is again another variation of the same beat pattern.

Vid. 3.2. Slatkin, 4/4 beat pattern15Slatkin, Lesson Two: The Basic 4 Pattern, Leonard Slatkin’s Conducting School, [02:16]

Since conducting is a relatively young profession, it still developed a lot in the last one-and-a-half century, allowing us to see such changes happen througout history by comparing video recordings. That goes amongst other things for the technique of beating time. Time beating emerged way earlier than the video camera was invented, but the practice as we know it know – using a set choreographical pattern for one hand, beating silently – became the common practice not long before that.

In the early days conducting was very much focused on time beating, and that in itself was not perfected yet. It started out as an audible cue, but was changed into a visible cue to not disturb the music. Gravitational acceleration is a key feature of efficient time beating, as it allows a spectator to predict precisely when the conductor will hit the beat. The technique of time beating was then elaborated on as techniques for beating simple and compound times appeared, and features of articulation appeared in the gesture. Furthermore, the standard position shifted from right before the eyes, towards around the waist. In the video below you can see how Artúr Nikisch has his hands high up as a way to guide the orchestra members’ gaze towards his eyes, which at that time in the history of conducting were primarily in charge of showing expression.

| Vid. 3.3. Nikisch, BeethovenSymphony No. 5, 191316Dot Conductor, Nikisch Conducts FILM 1913 + Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No 1., [00:01] | Vid. 3.4. Mäkelä, DvořákSymphony No. 9, 191317Concertgebouworkest, Antonín Dvorák – Symphony No. 9 ‘From The New World’ – Klaus Mäkelä | Made In America, [03:35] |

Then, as time passed, gestures were no longer purely functional, and ultimately every physical aspect of a conductor was expected to be involved with showing that expression: eyes, facial expressions, arms, and postures; all is involved.

Moreover, the position of the arms changed over time: Nikisch has his tact points as high as his head, but Slatkin places them somewhere around his torso. He was however of age already when he recorded this video, so naturally this will probably be more representative of common technique of the latter era rather than the current uses. When we compare this to one of the younger top ranking conductors Klaus Mäkelä, we see how in his case the position of tact point has been lowered still a bit further up until around his belly button. Naturally the conductor varies that height throughout the piece they are conducting, but there change is significant as conductors in the earlier days would not come that low whatsoever.

Case in point is that there is huge variation in the uses of beat patterns, throughout history but also between conductors of the same time period. When examining the use of beat patterns by a conductor, I will therefore consider the following questions:

- Does the conductor make use of beat patterns?

- Does the conductor show much expression in his time beating or is used more as a functional gesture?

- Does the conductor make use of a baton?

The baton is used to provide a focus point for the orchestra members so that for example time beating is more precise and clearer. When using only hands to beat time, the viewer has to decide for themself whether they focus on the middle of their conductor’s hand, their wrist, the tip of their pinky or whatnot. Furthermore, there is usually a lot of movement going on in the hands themselves. A proper baton conductor will make sure to conduct from the tip of their baton when they want precise timing, which facilitates an unmistakably clear signal for the orchestra to follow.

3. Use of left/right hand

A conductor should be able to use their hands independently from each other. The two hands have different basic tasks, but sometimes they can be used interchangaebly. Generally speaking, for right–handed conductors, the right hand is in charge of beating time, and the left hand for everything else that the right hand cannot do at that moment, ranging from indicating entries, to emphasizing the right hands cues, to indicating phrasings.

Conducting mirror handed (two hands doing the same thing at the same time) should be handled with care. Although it is often done by conductors in an attempt to make more clear what the want, the two hands will in practice never do exactly the same and can as a result be just confusing to the orchestra. Therefore, it generally is better avoided. However, sometimes it can be useful as a way of emphasizing the message of the right hand, such as an extra heavy accent or marcato notes. One must keep in mind here that emphasis works best when it is something different from what you do normally, so not using two hands to do the same thing all the time, but in moderation and with reason.

4. Dynamics

Dynamics are generally indicated by the size of the gesture (which can be a beat pattern or something else). There are two different ways to perform a change dynamic: firstly as step-wise process,: one phrase is mezzopiano, and the next mezzoforte because you make slightly larger gestures in the second phrase. Secondly, the conductor can cue a gradual in-/decrease of dynamics. That can be done by in-/decreasing the size of a beat patter, or by raising or lowering the left hand as to represent the change in volume.

Furthermore, the conductor is in charge of the dynamics in a musical work as a whole. Each piece will have some story to tell with some sort of climax which would be the loudest point of the piece. Especially in longer pieces the conductors must be aware of this as not every forte is supposed to be equally as loud because of this, so the conductor must have an understanding of how the dynamics relate to each other withing a piece, even between several movements in a multi-movement work, and communicate that to the orchestra, because it is the conductors responsibility to control the dynamics and get that climax right.

Moreover, the conductor must take in consideration the endurance of the orchestra members. For string players it is less importance, but for wind players, playing loud really takes an effort on their lips and mouths, so it would be unwise to plan one piece that requires loud dynamics for a long time at the beginning of a concert: all your wind players would exhausted after that and not capable of performing the rest of the pieces on the program well.

Lastly, the conductor must also take in consideration the place of performance. Some concert hall require more volume, others have a lot of echo so require less loud dynamics and dryer articulation. Which brings us to the next topic:

5. Articulation

Articulation is indicated by the velocity and way of change in velocity of the movement in start and end of a gesture. For example: an abrupt start indicates an accent, and an abrupt ending indicates a short length. Similarly, a non-abrupt start would indicate a gentle beginning of the note, and a continuous movement to the next beat (so no explicit end at all) indicates that the note should be sustained for it’s entire length. (The velocity in the middle decides the length and therefore the tempo).

Conductors must be aware of the different performance practices in different style periods throughout history. Different types of articulation were conventional at different times, and the conductor must be aware of this both academically as in a practice.

6. Phrasing

Indicating phrasing requires good skill, as it is not done by it’s own type of movement like the beats in time beating, but by nuances in the gestures. Like with dynamics, the gestures usually get larger in size when reaching the height of the phrase, but it also needs some way of getting more intense.

7. Use of the eyes and facial expressions

Facial expressions are large in variety and number and are easy to read for most humans. Therefore, it is a very powerful tool for a conductor. With their arms, conductors can provide great functional gestures like time beating and articulation, but in terms of expression the face can express the most nuances.

Making eye contact will make it clear to an orchestra member that your indications are meant for them. Moreover, not making eye contact is also a very useful cue in itself. When you make eye contact the musicians feel like you give them extra attention, so they must be important, so they’ll play louder. As Richard Strauss famously explained in Ten Golden Rules (for the album of a young conductor): “Never look at the trombones; it only encourages them.”18This exact quote is part of an oral tradition that can be found written down in newspaper [Newstalk, Newstalk]. The written version by Strauss himself is a little different: “Never look encouragingly at the brass, except with a short glance to give an important cue.” [Holden, Kapellmeister Strauss, 267]

Conductor Herbert von Karajan is well known for making relatively little eye contact when conducting, by his own account so that he can concentrate on the sound better and therefor respond quicker and more accurately to the orchestra. In one of his own anecdotes he explained how he was able to save a wind player in respiratory distress from not being able to finish the phrase by speeding up immediately as he heard them being in trouble. In the excerpt below, you can see how Karajan indeed has his eyes closed at the beginning, but makes sure to make eye contact with the first oboe for the entry of his solo. Furthermore, despite not making much eye contact, Karajan does not make the impression of being absent-minded. Somehow he still manages to show that he is solely concerned with the music ad the musicians using his general appearance rather than his eyes to make contact with the orchestra.

Vid. 3.5. Karajan, Beethoven Symphony No. 319Beethoven 9 Symphonies, Beethoven Symphony No 3 Herbert Von Karajan, [14:39]

8. Quirks

All conductors have of course their own body language, but they often also have their own quirks, or idiosyncratic gestures. That does not mean they are not functional; they are often just an non-typical way to indicate a well-known principle.

Carlos Kleiber for example tends to indicate phrasing by moving one extended arm from right to left and vice versa, often while omitting the other arm.

Moreover, Valery Gergiev occasionally chooses to conduct with a toothpick. The toothpick has no real functional value as it is too small for the orchestra members to see, but it allegedly helps Gergiev focus the movement on his fingertips which then result in more precise gestures for the orchestra to follow. Furthermore, he has the typical shaking of one or both hands when asking for more energy.

| Vid. 3.6. Kleiber, J. Strauss IIAn der schönen blauen Donau20Laso, Carlos Klieber The Blue Danube, [01:43] | Vid. 3.7. Gergiev, Rimsky-Korsakov Capriccio Espagnol21Laso, Hunjamoryc, Gergiev – Rimsky-Korsakov: Capriccio Espagnol, Op. 34 [1/2] (2007 Mariinsky), [00:20] |